I first heard about Madagascar’s supposed treatment/cure for the coronavirus back in late March of 2020 – before it was given a brand name, and when the country had fewer than ten cases of the disease.

In spite of only a handful of COVID-19 cases at the time, the government announced that the Malagasy Institute for Applied Research (IMRA) had produced a prophylaxis and cure; a tea derived from artemisia and other indigenous herbs. Before long it was branded “Covid Organics” or CVO, and President Andry Rajoelina was swigging it from a bottle before cameras.

Madagascar’s President Andry Rajoelina

“Tests have been carried out,” Rajoelina said, “two people have now been cured by this treatment.”

Maybe so. Anyone who falls ill to the coronavirus has, on average, a 98 percent chance of recovering. They could have treated the same two people with chewing gum and achieved the same outcomes.

Without a sufficient cohort of patients, IMRA could not possibly have carried out a legitimate clinical study – even if they had access to every infected person on the island at the time, which they didn’t.

IMRA has not released or reported any data on its research, the efficacy of Covid Organics or its side effects.

The Secret to Madagascar’s “Success”: A Young Population

Across Africa, people, credulous news outlets, and governments are hailing Covid Organics as an “out of Africa” success story. Some think it’s the secret behind Madagascar’s supposed “high recovery rate,” and low fatality rate. (The fatality rate was zero, until recently when Madagascar reported its first deaths from COVID-19.)

I wish it were true. I have loved ones in Madagascar, and also dear friends in Cameroon (which is one the continent’s hot spots for COVID‑19).

If we are to believe the official numbers, Madagascar’s success (so far) with COVID‑19 is its low-ish fatality rate. This is likely the result of several factors, including the relatively quick action the government took to close the borders, and stop most commercial flights.

We know that older people are more likely to die from COVID‑19, and younger people are more likely to survive. Madagascar’s median age is 19.7 years, making it one of the youngest countries in the world.

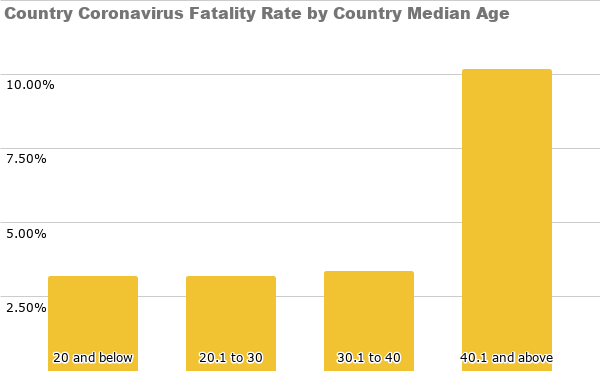

I searched for information on whether or not the COVID‑19 fatality rate by country correlated with the median age of countries. I assumed there would be a correlation (duh), but I wanted to see if Madagascar stands out at all from the trend.

I couldn’t find this data. So I geeked out and compiled the data myself, and created a graph.

Behold…

Median Age Data: The World Factbook – Central Intelligence Agency

Fatality Rate Data: COVID-19 CoronaTracker (via the CoronaTracker API)

View my spreadsheet that generated this graph (no longer maintained regularly)

Does Madagascar stand out among countries with a similar median age? Not really.

As of this writing, there are several countries with numbers of cases (per million) similar to Madagascar, and also with three or fewer deaths: Benin, East Timor, Eritrea, and Nepal.

What do these countries all have in common? A low median age.

Someone who has heard the hype about Covid Organics might ask, “But what about Madagascar’s high recovery rate?”

Madagascar’s current recovery rate is about 30 percent – with nearly two-thirds of all COVID‑19 patients they’ve ever reported still sick with the disease. There are nearly 150 countries with better recovery rates, and only about 50 countries with worse recovery rates at this point.

So it would seem, rather, that Madagascar has a below-average recovery rate. But comparing recovery rates is not useful. Not now. For one thing, not every country got its first case of COVID‑19 at the same time.

Ultimately (when the pandemic is over) the recovery rate for every country will be in the neighborhood of 98 percent – without any new cure or treatment created specifically for this disease. Younger countries (by median age) will have a higher recovery rate; older countries will have a lower recovery rate.

Potential Negative Effects of the Covid Organics Panacea

What happens if millions of Africans have an artemisia-based COVID‑19 panacea running through their veins?

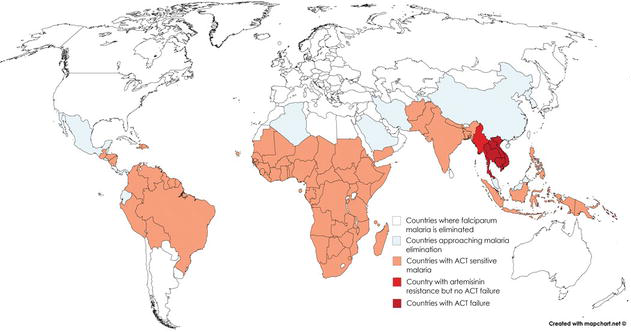

Artemisia is used and cultivated around the world for anti-malaria treatments. There are concerns that the malaria parasite could mutate and become resistant to artemisia-based treatments – as has happened in Southeast Asia.

See all the peach-colored countries in the map below? That’s where artemisia-based malaria treatments are still effective. The countries colored red and dark red are where these treatments have either lost some of their efficacy against malaria (red), or now they fail entirely (dark red) against malaria.

Africa is where 90 percent of the world’s malaria cases and deaths occur – more than 400,000 deaths per year.

It would be disastrous for Africa if the malaria parasite were to develop resistance to artemisia-based treatments. And that could possibly happen – if the malaria parasite were carelessly exposed to a whole bunch of artemisia-flavored blood for no beneficial reason.

At least President Rajoelina isn’t leading his fellow citizens drink hydroxychloroquine or to inject bleach, like the American president. But the potential consequences are still serious.

Speaking of that…

One Panacea-Peddling Pandemic President at a Time, Please

Remember before Trump began talking up hydroxychloroquine as a cure for COVID‑19; before he claimed to be taking it himself?

In February some small studies showed promising results with hydroxychloroquine. Then two more studies cast doubt on the effectiveness of hydroxychloroquine. It was confusing. Fast forward three months, to this week, and, well… “a massive study found that coronavirus patients who took the malaria drug touted by Trump had a higher risk of death.” This massive study involved nearly 100,000 patients around the world.

The four worst COVID-19 outbreaks in the world right now are all in countries where their respective presidents continue to insist that a malaria drug is “miracle cure” for the virus. They promote and peddle drugs that are not proven effective against this virus – potentially dangerous, in fact. Starting with the worst, these countries are: United States, Russia, Brazil, and United Kingdom.

The moral of the story is that this kind of science takes time. It takes controlled studies, and lots of data. A government should not jump to a conclusion merely because of wishful thinking, or because there might be money to be made.

Madagascar is a long way from joining the elite rank of the world’s most botched pandemic responses. But pushing an unproven tea as a cure for COVID-19 is not a good indicator that the country is inclined to get it right.

Map Credit: Aung Pyae Phyo and François Nosten (July 18th 2018). The Artemisinin Resistance in Southeast Asia: An Imminent Global Threat to Malaria Elimination, Towards Malaria Elimination – A Leap Forward, Sylvie Manguin and Vas Dev, IntechOpen, DOI: 10.5772/intechopen.76519. (CC BY 3.0)

1 comment

Chuck

June 8, 2020 at 5:28 amYikes. What a mess.

That’s actually some really good reporting, Ted.